Cross Post: Telling the (Hi)story of Jim Crow

Last year at the National Council on Public History’s Annual Meeting, I met Priya Chhaya at the Speed Networking event. Priya is an Online Content Coordinator in the Preservation Division at the National Trust for Historic Preservation and can be found blogging at her site …and this is what comes next. Recently, she mentioned Interpreting Slave Life in a post about how history, particularly the history of Jim Crow is being interpreted in Hollywood & in literature. It was an amazing post that I am proud to be mentioned in, and I wanted to make sure I shared it with you all. Please enjoy and stop by her site, as it is one of my favorites and has been a long standing link in the blogroll. (And yes, I completely copied and pasted this…with Priya’s permission)

Telling the (Hi)story of Jim Crow

There is a moment when you settle into your seats at a movie theater where you leave your sense of realism behind. You know that what you are about to see is a construction. A piecing together of someone else’s vision based on a nugget of an idea. For movies based on history that suspension of belief depends on how much you trust the writers, directors and the story you are being presented.

It’s all about interpretation, right?

One of the blogs that I read on a regular basis is called Interpreting Slave Life, which talks about the craft of telling the story of slavery. It is a tough job, requiring nuanced approach and a lot of thought. How can an interpretative approach demonstrate the complexity, the relationships? If you only have ten minutes with a group, what do you want them to walk away learning? The author, Nicole Moore takes the challenge head on and presents a nuanced approach in the telling.

That nuanced approach is also imperative when interpreting any period of history, and recently I’ve found myself looking at the differences between three narratives of Jim Crow. The first is an entirely fictional account of African American maids in Jackson, Mississippi, the second a recent action movie depicting the lives of the Tuskegee Airman, and finally a history text that narrates the migration of African Americans north during the same period. Each of these uses different storytelling tools (some more problematic than others) to convey the story of Jim Crow.

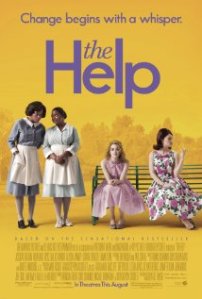

The Help

When putting together my “best of” list of books, movies etc., from this past year I putThe Help in both the book and movie category. In terms of storytelling I found the narrative to be engaging—while also providing a glimpse into the day-to-day indignities to African American’s by Jim Crow.

But it’s not a perfect story—one that has garnered a lot of discussion and anger on a variety of viewers. The Association for Black Women’s Historiansreleased a statement about the movie stating that The Help “distorts, ignores, and trivializes the experiences of black domestic workers,” specifically that it resurrects the “mammy” stereotype, misrepresents dialect of African American culture and speech, and “limits racial injustice to individual acts of meanness” by “group of attractive, well dressed, society women.”

In contrast, an article in the New Republicby John McWhorter makes the argumentthat the movie sought by The Help’s critics “might make a kind of sense if American society were actually as resistant to acknowledging racism as we are so often told. One might see the film as a precious opportunity to introduce a forgotten story, and understandably wince to see the focus on living rooms rather than streets, women in the afternoon rather than Klansmen at night, and sprinklings of harmony in a story that should be about gunshots and fire hoses.”

Like any good historian, I recognize that bringing these stories to life often brings with it controversy, which is an important part of ensuring a dialogue, and making sure that no one version dominates the telling of this history. Part of why I found the story so effective was that it parsed down, to a granular level just how specific “separate but equal” became. That the very real danger of Jim Crow was that any given moment, the offense taken by whites in the south could be used as a reason for penalty—even if it was as non-violent losing your job, a consequence of incredible impact when opportunities for African American women were so hard to come by.

I do agree that there is also the problem of agency—that the narrative is on one level about a white woman reaching out to African American women asking them to tell their story rather than a group of African American women acting on it themselves. However, it remains compelling because of the way the book and movie acknowledges how the ugliness, the brutality, and the violence of a time barely fifty years past could have manifested itself in a more insidious nature—where many southern Americans were complicit in perpetuating a system of culture and fear, of power right down to the simple act of going to the restroom.

Red Tails

I had held off on putting together this post because I wanted to wait to see the Anthony Hemingway film (The Wire, Ali) Red Tails. I had heard about this move a few years ago, not because I wanted to learn more about the Tuskegee Airman (I had other avenues for that) but because of my interest in science fiction. As a Star Wars fan, I had read about George Lucas’ interest in having this film made and I recognized how powerful a film this could be with his backing.

The movie is alright. Not great, but good. As a film about fighter pilots it succeeds in drawing you in to the bravery and the difficulties of fighting against German jet planes. It succeeds in showing how the Tuskegee Airman proved themselves, breaking stereotype after stereotype, in a simplistic way. In interviews prior to its release Lucas stated that he wanted to make a movie that showed 14 year old boys want courage was.

But what about how it tells the story of Jim Crow? Like The Help it lacks grit (and as a friend said, if you go in expectingSaving Private Ryan, you’ll be disappointed). It is filmed in a style that feels almost nostalgic and romantic, trying to present the narrative of fighting for your country while being treated as second class citizens.

I think this is part of its difficulty. Where The Help looks at Jim Crow and successfully illustrates its dehumanizing nature, Red Tails(though taking place roughly twenty years earlier) takes it and reduces it to single lines, and single acts that are almost apart from the heroes that it affects.

Yes, the movie tries to show that these men are being underutilized; their skills are marginalized, placing them at an Italian air base where all they do is sit around waiting for the opportunity to do what they were trained for. Yes, it underscores, without any hint of subtly the poor equipment, the crappy supplies and ridiculous missions they were given.

But the moments of overt racism—a single line in a board room in the Pentagon, a use of the n-word in the “whites only” officers club, feel like an obvious attempt to point out racism rather than allowing it to flow seamlessly in the narrative. What the movie lacks, unfortunately is the context—the larger story of the Tuskegee Airman and how they were formed, which would have added further weight (in the movie) to the accomplishments of the 332nd Fighter Group.

One last thought, I recognize that the issues I had with the portrayal in Red Tails can be construed as an argument for the movie to stray away from the singular story that Lucas wanted to tell–the snapshot of the moment where the 332nd was able to prove themselves as more than what was expected of them (and in a modern sense, prove that a big budget action movie can be made with an all African American cast and still be successful). However, I think that as far as telling the (hi)story of Jim Crow it just misses the bull’s-eye.

The Warmth of Other Suns

A few months ago I had the opportunity to listen to Isabel Wilkerson give a speech at theNational Preservation Conference in Buffalo, NY. A Pulitzer Prize winning author, Wilkerson wrote an incredible book about the great migration of African Americans from Jim Crow called The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration.

Two weeks ago, on Martin Luther King Day (which I found apt) I finished the book, and thought that it offered a great counter point to the other two narratives discussed in this blog. Unlike the two movies (and book), this is a non-fiction, history book. However, simply calling it non-fiction belittles its impact, in that while being a history book, it is very much falls within the realm of popular history—one that tells the story of an important piece of American history in a real and engaging way.

In short, the great migration was a period of American history that started in roughly 1915 and lasted through to the conclusion of Jim Crow in the 1960s. By the 1970s over six million African American’s had left their homes for new cities in the North and the West, and for ten years Isabel Wilkerson sought out their stories becoming, as historian Jill Lepore states in her review “a one-woman W.P.A. project. Her research took more than ten years, and is not unlike another chunk of work done by the Federal Writers’ Project: documenting the history of slavery, before its memory faded altogether.”

What I want to focus on is how Wilkerson tells the hi(story) of Jim Crow. Over the scope of seventy plus years she takes us through the lives of three individuals: Robert Pershing Foster, George Swanson Starling , and Ida Mae Brandon Gladney. In a narrative format (as opposed to using the voice of historical authority) Wilkerson allows us into individual lives, while using other sections to pull us out to see the broader context. It is an effective method, making us feel how individual decisions led to different paths out of the South, while telling us about the migration on a grander scale at the same time.

She does not hesitate to show the differences. That for some the decision to leave was a culmination of years of indignity, while for others it was due to a specific threat and fear. In using the individual stories she is able to show the vileness of Jim Crow and how no one was immune to the terror it brought to the African-American community. In the same vein she uses the mechanism to show what happened after—from the struggle to make ends meet in the north (including that all was not rosy and perfect after migration), and that each person chose to fight racism in different ways.

This can be seen through the life of Robert Pershing Foster, a surgeon who was married the daughter of the President of Atlanta University who believed “to his way of thinking, the way to change things was to be better than anybody at whatever you did, wear them down with your brilliance, and enjoy the heck out of doing it. So he had no patience for these sit-in displays, at least for his daughters anyway, much less actual violence.” (Wilkerson, 410)

What is great about this book, that movies like The Help and Red Tails cannot do with their limited scope, is that it shows the effect of Jim Crow on American history. That “many black parents who left the South got the one thing they wanted just by leaving. Their children would have a chance to grow up free of Jim Crow and to be their fuller selves. It cannot be known what course the lives of people like Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Diana Ross, Aretha Franklin, Michelle Obama, Jesse Owens, Joe Louis…and countless others might have taken had their parents or grandparents not participated in the great migration and raised in the North or West.” (Wilkerson, 535)

The other piece that I appreciated about the book was how she used quotations from African-American writers like Langston Hughes to frame each chapter’s discussion, to show how these people expressed themselves in song, in poetry, and through literature about the life they had left behind, and the new one they had come to embrace.

A lot of history books take the chronological approach, looking at a particular period of history through the eyes of many individual stories that are illustrations of a broader historical narrative. In choosing to use three specific stories, ones that she chose for the three “paths” taken by African-Americans to escape the south, you feel more connected, and are able to understand more about why Pershing, Starling, and Gladney chose the road they took.

~~~

Near the end of her book Isabelle Wilkerson states that the Great Migration was “if nothing else, an affirmation of the power of an individual decision, however powerless the individual might appear on the surface. “In the simple process of walking away one by one,” wrote the scholar Lawrence R. Rodgers, “millions of African-American southerners have altered the course of their own, and of all America’s, history.” (Wilkerson, 538)

I also believe strongly that even though some of these narratives miss the mark more than others, that these stories need to continue to be told in a popular mediums, to urge public dialogue and conversations about race in America in a very real way.

Articles of Interest

The Help

Open Statement to the Fans of The Help

‘The Help’ Isn’t Racist. Its Critics Are. (The New Republic)

A Critical Review of the Help (Blog)

Red Tails

National Park Service: Tuskegee Airman

Red Tails on National Public Radio

The Tuskegee Airmen Are for Everyone (Huff Post)

‘Red Tails’ a disservice to Tuskegee Airmen

Also see: The Tuskegee Airman (HBO/PBS)

The Warmth of Other Suns